Continuous Delivery with Docker and Jenkins

By: Rafal Leszko - ISBN: 978-1787125230 - Published On: 2017-08-27

1 Introducing Continuous Delivery

Jez Humble - “Continuos Delivery is the ability to get changes of all types – including new features, configuration changes, bug fixes, and experiments – into prod, or into the hands of the users, safely, and quickly in a sustainable way.

Shortcomings of the Traditional Delivery Process

- Slow delivery

- Long feedback cycle

- Lack of automation

- Risky hotfixes

- Stress

- Poor communication

- Shared responsibility

- Lower job satisfaction

Benefits of Continuous Delivery (If do well)

- Fast Delivery

- Fast feedback cycle

- Low-risk releases

- Flexible release options

The automated deployment pipeline

The automated deployment pipeline is a sequence of script that is run after every code change committed to a repo. If the process is successful, it ends up with the deployment to prod.

Each Step corresponds to a phase in the traditional process:

- Continuous Integration: checks to make sure that the code written by the different developers integrates together.

- Automated Acceptance Testing: This replaces the manual QA phase and checks if the features implemented by developers meet the client’s requirements.

- Configuration Management: This replaces the manual operations phase-configures the env and deploy the software.

Testing

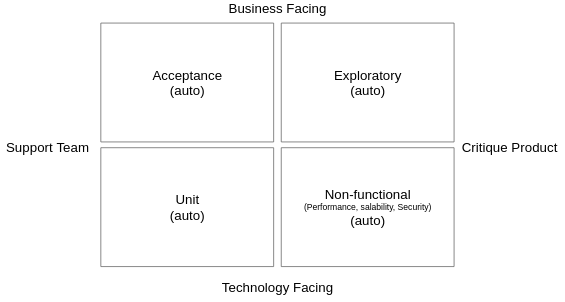

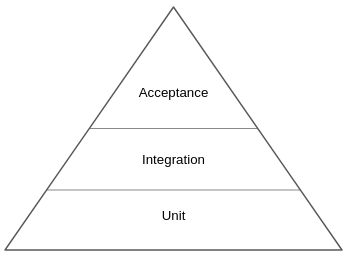

- Acceptance Testing (auto) - Does it do what it should

- Unit Testing (auto) - developers do it.

- Exploratory Testing (Manual) - This is the manual block-box testing, which tries to break or improve the system.

- Non-functional - Performance, scalability and security

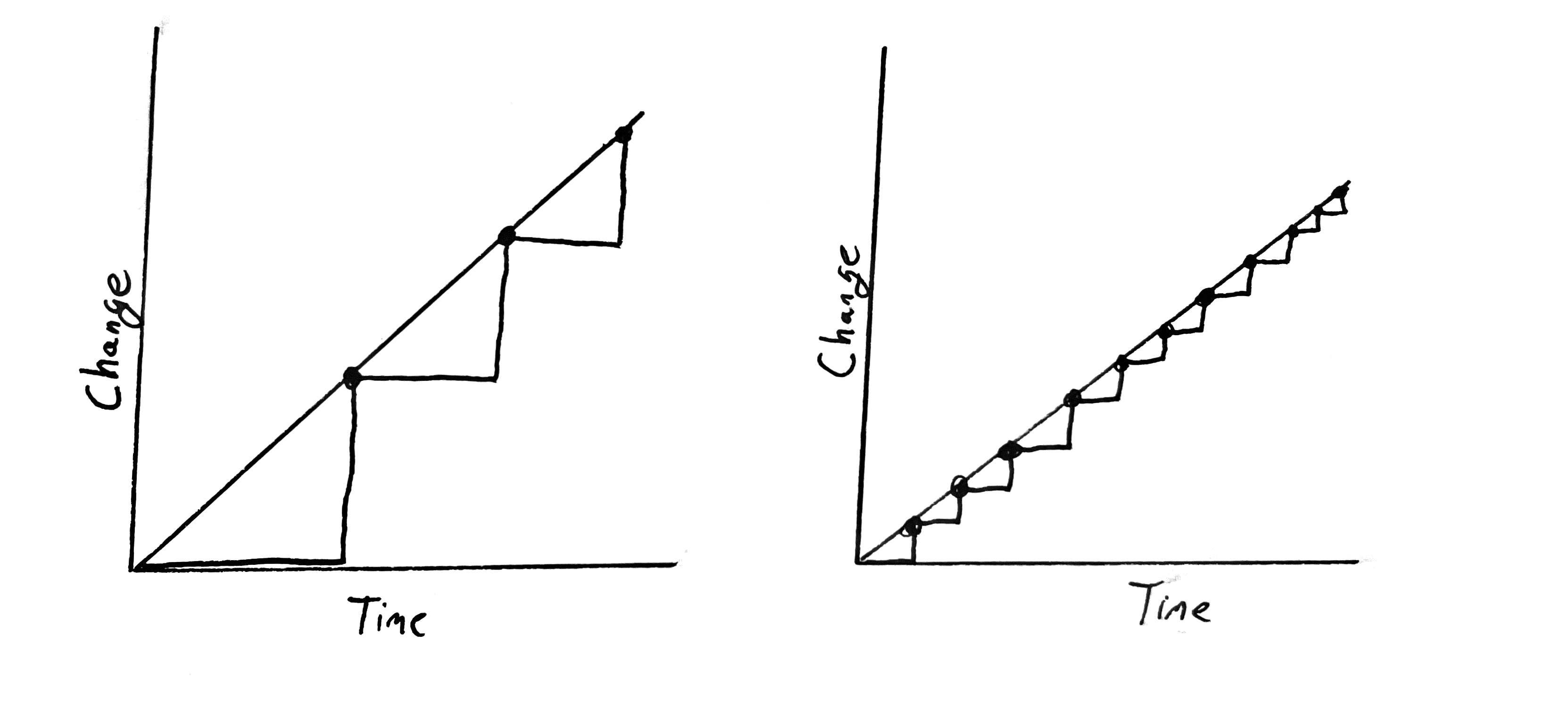

When we move up the pyramid, the test become slower and move expensive to create.

The case is different at the bottom of the pyramid. Unit tests are cheap and fast, so we should strive for near 100% code coverage. They are written by developers and providing them should be a standard procedure for any mature team.

Organization Prerequisites

Many organizations would like to use the Angie process, but they don’t change their culture. You can’t use scram in your dev team unless the org’s structure is adjust to that. Otherwise, even with good will, you won’t make it work.

A long time ago, when software was written by individuals or microteams, there was no clear separation between the development, quality assurance, and operations. A person developed the code, tested it, and then put it into the production. If anything went wrong, the same person investigated the issue, fixed it, and redeployed to the production.

The way the development is organized now changed gradually, when systems became larger and development teams grew. Then, engineers started to become specialized in one area. That made perfect sense, because specialization caused a boost in the productivity. However, the side effect was the communication overhead.

It is especially visible if developers, QAs, and operations are under separate departments in the organization, sit in different buildings, or are outsourced to different countries. Such organization structure is no good for the Continuous Delivery process. We need something better, we need to adapt the so-called DevOps culture.

Tech and Development Prerequisites

- Automated build, test, package, and deploy tasks.

- Quick pipeline execution

- Quick failure recovery

- Zero-downtime deployment -

🗨️ annot. - no sure if this is a HARD requirement base on org needs - Trunk-based development -

🗨️ annot. - no sure if this is a HARD requirement base on org needs

2 Introducing Docker

Docker is an open source project designed to help with application deployment using software containers. This quote is from the official Docker page: “Docker containers wrap a piece of software in a complete filesystem that contains everything needed to run: code, runtime, system tools, system libraries - anything that can be installed on a server.

Each application is launched as a separate image with all dependencies and a guest operating system. Images are run by the hypervisor, which emulates the physical computer architecture.

Environment - Installing and running software is complex. You need to decide about the operating system, resources, libraries, services, permissions, other software, and everything your application depends on. Then, you need to know how to install it. What’s more, there may be some conflicting dependencies. What do you do then? What if your software needs an upgrade of a library but the other does not?

Isolation - share resources, so if there is a memory leak in application A, it can freeze not only itself but also application B. They share network interfaces, so if applications A and B both use port 8080, one of them will crash. Isolation concerns the security aspects too. Running a buggy application or malicious software can cause damage to other applications.

Organizing app - Servers often end up looking messy with a ton of running applications nobody knows anything about. How will you check what applications are running on the server and what dependencies each of them is using? They could depend on libraries, other applications, or tools. Without the exhaustive documentation, all we can do is look at the running processes and start guessing.

Portability - Docker moves the concept of portability one level higher; if the Docker version is compatible, then the shipped software works correctly regardless of the programming language, operating system, or environment configuration. Docker, then, can be expressed by the slogan “Ship the entire environment instead of just code.

Kittens and cattle - “Treat your servers like cattle, not pets.”

Docker networking

Docker allows publishing to the specified host network interface with `<host_port>:<container_port>

If you check the network interfaces on your machine, you can see that one of the interfaces is called docker0. The docker0 interface is created by the Docker daemon in order to connect with the Docker container.

Note that by default, the containers are protected by the host’s firewall system and don’t open any routes from external systems. We can change this default behavior by playing with the --network flag and setting it as follows:

bridge(default): network via the default Docker bridgenone: no networkcontainer: network joined with the other (specified) containerhost: host network (no firewall)

Docker volumes

Docker volume is the Docker host’s directory mounted inside the container. It allows the container to write to the host’s filesystem as it was writing to its own.

3 Configuring Jenkins

Jenkins is an open source automation server written in Java. Formerly known as Hudson, it was renamed after Oracle bought Hudson and decided to develop it as the proprietary software. Jenkins remained under the MIT license and is highly valued for its simplicity, flexibility, and versatility. Jenkins outstands other Continuous Integration tools and is the most widely used software of its kind. That is all possible because of its features and capabilities.

Most interesting parts of the Jenkins’ characteristics.

- Language agnostic

- Extensible by plugins

- Portable

- Supports most SCM

- Distributed

- Simplicity

- Code-oriented

Jenkins Architecture

Master and slaves

Jenkins should not execute builds at all, but delegate them to the slave (agent) instances. To be precise, the Jenkins we’re currently running is called the Jenkins master and it can delegate to the Jenkins agents.

In a distributed builds environment, the Jenkins master is responsible for:

- Receiving build triggers

- Sending notifications

- Handling HTTP requests

- Managing the build environment

We can use Jenkins slaves to balance the load and scale up the Jenkins infrastructure. Such a process is called the horizontal scaling.

Vertical scaling means that, when the master’s load grows, then more resources are applied to the master’s machine. So, when new projects appear in our organization, we buy more RAM, add CPU cores, and extend the HDD drives.

Horizontal scaling means that, when an organization grows, then more master instances are launched. This requires a smart allocation of instances to teams and, in the extreme case, each team can have its own Jenkins master. In that case, it might even happen that no slaves are needed.

Test and production instances

There should always be two instances of the same Jenkins infrastructure: test and production. Test environment should always be as similar as possible to the production, so it also requires the similar number of agents attached.

Communication protocols

SSH: Master connects to slave using the standard SSH protocol. Jenkins has an SSH-client built-in, so the only requirement is the SSHD server configured on slaves. This is the most convenient and stable method because it uses standard Unix mechanisms.

Java Web Start: Java application is started on each agent machine and the TCP connection is established between the Jenkins slave application and the master Java application. This method is often used if the agents are inside the firewalled network and the master cannot initiate the connection.

Windows service: The master registers an agent on the remote machine as a Windows service. This method is discouraged since the setup is tricky and there are limitations on the graphical interfaces usage.

Agents

We start from the simplest option which is to permanently add specific agent nodes. The idea behind this solution is to permanently add general-purpose slaves.

Jenkins Swarm allows you to dynamically add slaves without the need to configure them in the Jenkins master.

Another option is to set up Jenkins to dynamically create a new agent each time a build is started. Such a solution is obviously the most flexible one since the number of slaves dynamically adjust to the number of builds. Let’s have a look at how to configure Jenkins this way.

Dynamically provisioned Docker agents can be treated as a layer over the standard agent mechanism. It changes neither the communication protocol nor how the agent is created.

Building Jenkins slave Docker Image

So far, we have used the Jenkins images pulled from the internet. We used jenkins for the master container and evarga/jenkins-slave for the slave container.

Let’s start from the slave image, because it’s more often customized. The build execution is performed on the agent, so it’s the agent that needs to have the environment adjusted to the project we would like to build. For example, it may require the Python interpreter if our project is written in Python. The same is applied to any library, tool, testing framework, or anything that is needed by the project.

There are three steps to build and use the custom image:

- Create a Dockerfile.

- Build the image.

- Change the agent configuration on master.

Blue Ocean UI

Blue Ocean is the plugin, which redefines the user experience of Jenkins. If Jenkins is aesthetically displeasing to you, then it’s definitely worth giving a try.

4 Continuous Integration Pipeline

A pipeline is a sequence of automated operations that usually represents a part of software delivery and the quality assurance process.

Its a chain of scripts providing the following additional benefits:

- Operation grouping: Operations are grouped together into stages that introduce a structure into the process and clearly defines the rule: if one stage fails, no further stages are executed

- Visibility: All aspects of the process are visualized, which help in quick failure analysis and promotes team collaboration

- Feedback: Team members learn about any problems as soon as they occur, so they can react quickly

Jenkins Pipeline structure

Step: A single operation (tells Jenkins what to do, for example, checkout code from repository, execute a script)

Stage: A logical separation of steps (groups conceptually distinct sequences of steps, for example, Build, Test, and Deploy) used to visualize the Jenkins pipeline progress.

It’s possible to create parallel steps; however, it’s better to treat it as an exception when really needed for optimization purposes.

Sections

- Stages: This defines a series of one or more stage directives

- Steps: This defines a series of one or more step instructions

- Post: This defines a series of one or more step instructions that are run at the end of the pipeline build; marked with a condition (for example, always, success, or failure), usually used to send notifications after the pipeline build (we will cover this in detail in the Triggers and notifications section.)

Directives

Directives express the configuration of a pipeline or its parts:

AgentThis specifies where the execution takes place and can define the label to match the equally labeled agents or docker to specify a container that is dynamically provisioned to provide an environment for the pipeline executionTriggersThis defines automated ways to trigger the pipeline and can use cron to set the time-based scheduling or pollScm to check the repository for changes (we will cover this in detail in the Triggers and notifications section)OptionsThis specifies pipeline-specific options, for example, timeout (maximum time of pipeline run) or retry (number of times the pipeline should be rerun after failure)EnvironmentThis defines a set of key values used as environment variables during the buildParametersThis defines a list of user-input parametersStageThis allows for logical grouping of stepsWhenThis determines whether the stage should be executed depending on the given condition

Steps

Steps are the most fundamental part of the pipeline. They define the operations that are executed, so they actually tell Jenkins what to do.

shThis executes the shell command; actually, it’s possible to define almost any operation using shcustomJenkins offers a lot of operations that can be used as steps (for example, echo); many of them are simply wrappers over the sh command used for convenience; plugins can also define their own operationsscriptThis executes a block of the Groovy-based code that can be used for some non-trivial scenarios, where flow control is needed

Jenkinsfile

All the time, so far, we created the pipeline code directly in Jenkins. This is, however, not the only option. We can also put the pipeline definition inside a file called Jenkinsfile and commit it to the repository together with the source code. This method is even more consistent because the way your pipeline looks is strictly related to the project itself.

Triggers and Notifications

An automatic action to start the build is called the pipeline trigger. In Jenkins, there are many options to choose from; however, they all boil down to three types:

- External - Jenkins starts the build after it’s called by the notifier, which can be the other pipeline build, the SCM system (for example, GitHub), or any remote script.

- Polling SCM (Source Control Management) - Jenkins periodically calls GitHub and checks if there was any push to the repository. Then, it starts the build.

- Main use case - Jenkins is inside the firewalled network (which GitHub does not have access to)

- Commits are frequent and the build takes a long time, so executing a build after every commit would cause an overload

- Scheduled build - Scheduled trigger means that Jenkins runs the build periodically, no matter if there was any commit to the repository or not.

Development Workflows

Trunk-based workflow - There is one central repository with a single entry for all changes to the project, which is called the trunk or master. Every member of the team clones the central repository to have their own local copies. The changes are committed directly to the central repository.

- If everyone commits to the main codebase, then the pipeline often fails. In this case, the old Continuous Integration rule says, “If the build is broken, then the development team stops whatever they are doing and fixes the problem immediately."

Branching workflow - When developers work on a new feature, they create a branch from the trunk and commit all changes there. This makes it easy for developers to work on a feature without breaking the main codebase. When the feature is completed, a developer rebases the feature branch from master and creates a pull request that contains all feature-related code changes When the code is accepted by other developers and automatic system checks, then it is merged into the main codebase. Then, the build is run again on master but should almost never fail since it didn’t fail on the branch.

- Solves the broken trunk issue but introduces another one: if everyone develops in their own branches, then where is the integration? A feature usually takes weeks or months to develop, and for all this time, the branch is not integrated into the main code, therefore it cannot be really called “continuous” integration; not to mention that there is a constant need for merging and resolving conflicts.

Forking workflow - Forking means literally creating a new repository from the other repository. Developers push to their own repositories and when they want to integrate the code, they create a pull request to the other repository. The main advantage of the forking workflow is that the integration is not necessarily via a central repository. It also helps with the ownership because it allows accepting pull requests from others without giving them write access.

- Shares the same issues as the branching workflow.

Jenkins Multibranch

If you decide to use branches in any form, the long feature branches or the recommended short-lived branches, then it is convenient to know that the code is healthy before merging it into master. This approach results in always keeping the main codebase green and, luckily, there is an easy way to do it with Jenkins.

Non-technical requirements

James Shore in his article Continuous Integration on a Dollar a Day described how to set up the Continuous Integration process without any additional software. All he used was a rubber chicken and a bell. Continuous Integration on a Dollar a Day

The idea is a little oversimplified, and automated tools are useful; however, the main message is that without each team member’s engagement, even the best tools won’t help.

People need to:

- Check in regularly:

- Create comprehensive unit tests

- Keep the process quick (less then 10min)

- Monitor/alert the builds

5 Automated Acceptance Testing

Acceptance testing is a test performed to determine if the business requirements or contracts are met. Sometimes, also called UAT (user acceptance testing), end user testing, or beta testing, it is a phase of the development process when software meets the real-world audience.

Docker registry

Docker registry is a storage for Docker images. To be precise, it is a stateless server application that allows the images to be published (pushed) and later retrieved (pulled) when needed.

Artifact Repository

While the source control management stores the source code, the artifact repository is dedicated for storing software binary artifacts, for example, compiled libraries or components, later used to build a complete application.

Why do we need to store binaries on a separate server using a separate tool?:

- File size: Artifact files can be large, so the systems need to be optimized for their download and upload.

- Versions: Each uploaded artifact needs to have a version that makes it easy to browse and use. Not all versions, however, have to be stored forever; for example, if there was a bug detected, we may not be interested in the related artifact and remove it.

- Revision mapping: Each artifact should point to exactly one revision of the source control and, what’s more, the binary creation process should be repeatable.

- Packages: Artifacts are stored in the compiled and compressed form so that these time-consuming steps need not be repeated.

- Access control: Users can be restricted differently to the source code and artifact binary access.

- Clients: Users of the artifact repository can be developers outside the team or organization, who want to use the library via its public API.

- Use cases: Artifact binaries are used to guarantee that exactly the same built version is deployed to every environment to ease the rollback procedure in case of failure.

Docker Compose

Docker Compose is a tool for defining, running, and managing multi-container Docker applications. Services are defined in a configuration file (a YAML format) and can be created and run all together with a single command.

Docker Compose provides dependencies between the containers; in other words, it links one container to another container. Technically, this means that containers share the same network and that one container is visible from the other. To continue our example, we need to add this dependency in the code, and we will do this in a few steps.

Writing user-facing tests

Most software is written to deliver a specific business value, and that business value is defined by non-developers. The Acceptance Criteria are written by users (or a product owner as their representative) with the help of developers. Developers write the testing implementation called fixtures or step definitions that integrates the human-friendly DSL specification with the programming language. As a result, we have an automated test that can be well-integrated into the Continuous Delivery pipeline.

6 Configuration Management with Ansible

Configuration management is a process of controlling configuration changes in a way that the system maintains integrity over time.

Application configuration - This involves software properties that decide how the system works, which are usually expressed in the form of flags or properties files passed to the application, for example, the database address, the maximum chunk size for file processing, or the logging level.

Infrastructure configuration - This involves server infrastructure and environment configuration, which takes care of the deployment process. It defines what dependencies should be installed on each server and specifies the way applications are orchestrated.

Traits of good configuration management

- Automation

- Version control

- Incremental changes

- Easy Server provisioning

- Security

- Simplicity

Overview of configuration management tools

The most popular configuration management tools are Ansible, Puppet, and Chef.

- Configuration Language: Chef uses Ruby, Puppet uses its own DSL (based on Ruby), and Ansible uses YAML.

- Agent-based: Puppet and Chef use agents for communication, which means that each managed server needs to have a special tool installed. Ansible, on the contrary, is agentless and uses the standard SSH protocol for communication.

Benefits of Ansible

- Environment configuration

- Non-Dockerized applications

- Inventory

- GUI - not really you need to pay for it.

- Improve testing process

7 Continuous Delivery Pipeline

Environments and infrastructure

There are four most common environment types: production, staging, QA (testing), and development.

- Production is the environment that is used by the end user. It exists in every company and, of course, it is the most important environment.

- The staging environment is the place where the release candidate is deployed in order to perform the final tests before going live. Ideally, this environment is a mirror of the production.

- For the purpose of the Continuous Delivery process, the staging environment is indispensable.

- The QA environment (also called the testing environment) is intended for the QA team to perform exploratory testing and for external applications (which depend on our service) to perform integration testing.

- The development environment can be created as a shared server for all developers or each developer can have his/her own development environment.

In the Continuous Delivery process, the slave must have access to servers, so that it can deploy the application.

There are different approaches for providing slaves with the server’s credentials:

- Put SSH key into slave: If we don’t use dynamic Docker slave provisioning, then we can configure Jenkins slave machines to contain private SSH keys.

- Put SSH key into slave image: If we use dynamic Docker slave provisioning, we could add the SSH private key into the Docker slave image. However, it creates a possible security hole, since anyone who has access to that image would have access to the production servers.

- Jenkins credentials: We can configure Jenkins to store credentials and use them in the pipeline.

- Copy to Slave Jenkins plugin: We can copy the SSH key dynamically into the slave while starting the Jenkins build.

Nonfunctional testing

Decide which nonfunctional aspects are crucial to our business For each of them:

- Specify the tests the same way we did for acceptance testing

- Add a stage to the Continuous Delivery pipeline. The application comes to the release stage only after all nonfunctional tests pass.

Performance testing

They measure the responsiveness and stability of the system. The simplest performance test we could create is to send a request to the web service and measure its round-trip time (RTT).

Load testing

Load tests are used to check how the system functions when there are a lot of concurrent requests. While a system can be very fast with a single request, it does not mean that it works fast enough with 1,000 requests at the same time.

Stress testing

Stress testing, also called capacity testing or throughput testing, is a test that determines how many concurrent users can access our service. It may sound the same as load testing; however, in the case of load testing, we set the number of concurrent users (throughput) to a given number, check the response time (latency), and make the build fail if the limit is exceeded.

Stress testing is not well suited for the Continuous Delivery process. It should be prepared as a separate script of a separate Jenkins pipeline.

Scalability testing

Scalability testing explains how latency and throughput change when we add more servers or services. The perfect characteristic would be linear, which means if we have one server and the average request-response time is 500 ms when used by 100 parallel users, then adding another server would keep the response time the same and allow us to add another 100 parallel users. In reality, it’s often hard to achieve this because of keeping data consistency between servers.

Scalability testing should be automated and should provide the graph presenting the relationship between the number of machines and the number of concurrent users. Such data is helpful in determining the limits of the system and the point at which adding more machines does not help.

It should be prepared as a separate script of a separate Jenkins pipeline

Endurance testing

Endurance tests, also called longevity tests, run the system for a long time to see if the performance drops after a certain period of time. They detect memory leaks and stability issues.

Since they require a system running for a long time, it doesn’t make sense to run them inside the Continuous Delivery pipeline.

Security testing

Security testing deals with different aspects related to security mechanisms and data protection. Some security aspects are purely functional requirements these parts should be checked the same way as any other functional requirement.

Security tests should be included in Continuous Delivery as a pipeline stage.

Maintainability testing

Maintainability tests explain how simple a system is to maintain. In other words, they judge code quality. The Sonar tool can also give some overview of the code quality and the technical debt.

Recovery testing

Recovery testing is a technique to determine how quickly the system can recover after it crashed because of a software or hardware failure. The best case would be if the system does not fail at all, even if a part of its services is down. Some companies even perform production failures on purpose to check if they can survive a disaster. The best known example is Netflix and their Chaos Monkey tool, which randomly terminates random instances of the production environment.

Recovery testing is obviously not part of the Continuous Delivery process, but rather a periodic event to check the overall health.

Nonfunctional challenges

- Long test run

- Incremental nature:

- Vague requirements

- Multiplicity

The best approach to address nonfunctional aspects is to take the following steps:

- Make a list of all nonfunctional test types.

- Cross out explicitly the test you don’t need for your system.

- Split your tests into two groups:

- Continuous Delivery: It is possible to add it to the pipeline

- Analysis: It is not possible to add to the pipeline because of their execution time, their nature, or the associated cost

- For the Continuous Delivery group, implement the related pipeline stages.

- For the Analysis group:

- Create automated tests

- Schedule when they should be run

- Schedule meetings to discuss their results and take action points

A very good approach is to have a nightly build with the long tests that don’t fit the Continuous Delivery pipeline. Then, it’s possible to schedule a weekly meeting to monitor and analyze the trends of system performance.

Application versioning strategies

Semantic versioning

The most popular solution is to use sequence-based identifiers (usually in the form of x.y.z). This method requires a commit to the repository done by Jenkins in order to increase the current version number, which is usually stored in the build file.

- x: This is the major version; the software does not need to be backward-compatible when this version is incremented

- y: This is the minor version; the software needs to be backward compatible when the version is incremented

- z: This is the build number; this is sometimes also considered as a backward and forward-compatible change

Timestamp

Using the date and time of the build for the application version is less verbose than sequential numbers, but very convenient in the case of the Continuous Delivery process, because it does not require committing back to the repository by Jenkins.

Hash

A randomly generated hash version shares the benefit of the datetime and is probably the simplest solution possible. The drawback is that it’s not possible to look at two versions and tell which is the latest one.

Mixed

There are many variations of the solutions described earlier, for example, major and minor versions with the datetime.

Smoke testing

A smoke test is a very small subset of acceptance tests whose only purpose is to check that the release process is completed successfully. Otherwise, we could have a situation in which the application is perfectly fine; however, there is an issue in the release process, so we may end up with a non-working production.

8 Clustering with Docker Swarm

A server cluster is a set of connected computers that work together in a way that they can be used similarly to a single system.

Docker Swarm provides a number interesting features. Let’s walk through the most important ones:

- Load balancing:

- Dynamic role management:

- Dynamic service scaling

- Failure recovery

- Rolling updates:

- Two service modes:

- Replicated services: The specified number of replicated containers are distributed among the nodes based on the scheduling strategy algorithm

- Global services: One container is run on every available node in the cluster

- Security

Introducing Docker Stack

Docker Stack is a method to run multiple-linked containers on a Swarm cluster.

Docker Swarm orchestrates which container is run on which physical machine. The containers, however, don’t have any dependencies between themselves, so in order for them to communicate, we would need to link them manually.

Alternative cluster management systems

Kubernetes

Kubernetes is an open source cluster management system originally designed by Google. Even though it’s not Docker-native, the integration is smooth, and there are many additional tools that help with this process;

Apache Mesos

Apache Mesos is an open source scheduling and clustering system started at the University of California, Berkeley, in 2009, long before Docker emerged. It provides an abstraction layer over CPU, disk space, and RAM. One of the great advantages of Mesos is that it supports any Linux application, not necessarily (Docker) containers.

Dynamic slave provisioning

When the build is started, the Jenkins master runs a container from the Jenkins slave Docker image, and the Jenkinsfile script is executed inside the container.

9 Advanced Continuous Delivery

Managing database changes

A web service, however, is usually linked to its stateful part, a database that poses new challenges to the delivery process. These challenges can be grouped into the following categories

- Compatibility: The database schema and the data itself must be compatible with the web service all the time

- Zero-downtime deployment: In order to achieve zero-downtime deployment, we use rolling updates, which means that a database must be compatible with two different web service versions at the same time

- Rollback: A rollback of a database can be difficult, limited, or sometimes even impossible because not all operations are reversible (for example, removing a column that contains data)

- Test data: Database-related changes are difficult to test because we need test data that is very similar to production

Understanding schema updates

Relational databases have static schemas. If we would like to change it, for example, to add a new column to the table, we need to write and execute a SQL DDL (data definition language) script. Doing this manually for every change requires a lot of work and leads to error-prone solutions, in which the operations team has to keep in sync the code and the database structure.

A much better solution is to automatically update the schema in an incremental manner. Such a solution is called database migration.

Database schema migration is a process of incremental changes to the relational database structure

Migration scripts should be stored in the version control system, usually in the same repository as the source co

Changing database in Continuous Delivery

The first approach to use database updates inside the Continuous Delivery pipeline could be to add a stage within the migration command execution. This simple solution would work correctly for many cases; however, it has two significant drawbacks:

- Rollback: As mentioned before, it’s not always possible to roll back the database change (Flyway doesn’t support downgrades at all). Therefore, in the case of service rollback, the database becomes incompatible.

- Downtime: The service update and the database update are not executed exactly at the same time, which causes downtime.

This leads us to two constraints that we will need to address:

- The database version needs to be compatible with the service version all the time

- The database schema migration is not reversible

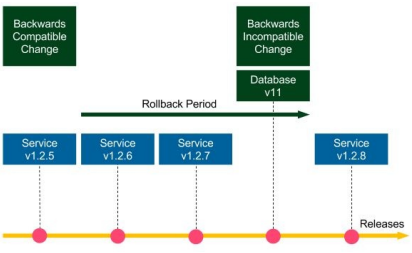

Backwards-compatible changes

Suppose the schema migration Database v10 is backwards-compatible. If we need to roll back the Service v1.2.8 release, then we deploy Service v1.2.7, and there is no need to do anything with the database (database migrations are not reversible, so we keep Database v11). Since the schema update is backwards-compatible, Service v.1.2.7 works perfectly fine with Database v11. The same applies if we need mto roll back to Service v1.2.6, and so on. Now, suppose Database v10 and all other migrations are backwards-compatible, then we could roll back to any service version and everything would work correctly.

Non-backwards-compatible changes

Non-backwards-compatible changes are way more difficult. If database change v11 was backwards-incompatible, it would be impossible to roll back the service to 1.2.7. In this case, how can we approach non-backwards-compatible database migrations so that rollbacks and zerodowntime deployments would be possible?

We can address this issue by converting a nonbackwards-compatible change into a change that is backwards-compatible for a certain period of time. In other words, we need to put in the extra effort and split the schema migration into two parts:

- Backwards-compatible update executed now, which usually means keeping some redundant data

- Non-backwards-compatible update executed after the rollback period time that defines how far back we can revert our code

Let’s think about an example of dropping a column. A proposed method would include two steps:

- Stop using the column in the source code (v1.2.5, backwards-compatible update, executed first).

- Drop the column from the database (v11, non-backwards-compatible update, executed after the rollback period).

Separating database updates from code changes

The recommended approach is to make a clear separation that a commit to the repository is either a database update or a code change.

The database-code separation does not mean that we must have two separate Jenkins pipelines. The pipeline can always execute both, but we should keep it as a good practice that a commit is either a database update or a code change.

Avoiding shared database

In many systems, we can spot that the database becomes the central point that is shared between multiple services. In such a case, any update to the database becomes much more challenging because we need to coordinate it between all services.

Integration/acceptance testing

Integration and acceptance tests usually use the test/staging database, which should be as similar as possible to the production. One approach, taken by many companies, is to snapshot the production data into staging that guarantees that it is exactly the same. This approach, however, is treated as an anti-pattern for the following reasons:

- Test isolation: Each test operates on the same database, so the result of one test may influence the input of the others

- Data security: Production instances usually store sensitive information and are therefore better secured

- Reproducibility: After every snapshot, the test data is different, which may result in flaky tests

The best way to add data to the staging database is to use the public API of a service and keep your test data up-to-date no easy task.

Parallelizing pipelines

In some cases, the stages are time-consuming and it’s worth running them in parallel. A very good example is performance tests. They usually take a lot of time, so assuming they are independent and isolated, it makes sense to run them in parallel.

Parallel steps: Within one stage, parallel processes run on the same agent. This method is simple because all Jenkins workspace-related files are located on one physical machine, however, as always with the vertical scaling, the resources are limited to that single machine.

Parallel stages: Each stage can be run in parallel on a separate agent machine that provides horizontal scaling of resources. We need to take care of the file transfer between the environments (using the stash Jenkinsfile keyword) if a file created in the previous stage is needed on the other physical machine.

Reusing pipeline components

Parametrized build can help reuse the pipeline code for scenarios when it differs just a little bit. This feature, however, should not be overused because too many conditions can make the Jenkinsfile difficult to understand.

Shared libraries

A shared library is a Groovy code that is stored as a separate source-controlled project. This code can be later used in many Jenkinsfile scripts as pipeline steps

If “Load implicitly” hadn’t been checked in the Jenkins configuration, then we would need to add “@Library(’example’) _” at the beginning of the Jenkinsfile script.

Shared libraries are not limited to one step. Actually, with the power of the Groovy language, they can even act as templates for entire Jenkins pipelines.

Adding manual steps

stage("Release approval") {

steps {

input "Do you approve the release?"

}

}

Blue-green deployment

Blue-green deployment is a technique to reduce the downtime associated with the release. It concerns having two identical production environments, one called green, the other called blue.

Canary release

Canary releasing is a technique to reduce the risk associated with introducing a new version of the software. Similar to blue-green deployment. Also, similar to the blue-green deployment technique, the release process starts by deploying a new version in the environment that is currently unused. Here, however, the similarities end.

The load balancer, instead of switching to the new environment, is set to link only a selected group of users to the new environment. All the rest still use the old version. This way, a new version can be tested by some users and in case of a bug, only a small group is affected.

After the testing period, all users are switched to the new version.

Working with legacy systems

Legacy systems are, however, way more challenging because they usually depend on manual tests and manual deployment steps.

The way to apply the Continuous Delivery process depends a lot on the current project’s automation, the technologies used, the hardware infrastructure, and the current release process. Usually, it can be split into three steps:

- Automating build and deployment.

- Build and package

- DB Migrations

- Deploy

- Repeatable config

- Automating tests.

- Acceptance/sanity test suite

- (Virtual) test environments

- Refactoring and introducing new features.

- Refactoring

- Rewrite

- Introducing new features: During the new feature implementation, it’s worth using the feature toggle pattern. Then, in case anything bad happens, we can quickly turn off the new feature. Actually, the same pattern should be used during refactoring

Bonus Best practices

Practice 1 – own process within the team!

Own the entire process within the team, from receiving requirements to monitoring the production. As once said: “A program running on the developer’s machine makes no money.” This is why it’s important to have a small DevOps team that takes complete ownership of a product

Practice 2 – automate everything!

Automate everything from business requirements (in the form of acceptance tests) to the deployment process. Manual descriptions, wiki pages with instruction steps, they all quickly become out of date and lead to tribal knowledge that makes the process slow, tedious, and unreliable.

Practice 3 – version everything!

Version everything: software source code, build scripts, automated tests, configuration management files, Continuous Delivery pipelines, monitoring scripts, binaries, and documentation. Simply everything.

Practice 4 – use business language for acceptance tests!

Work closely with the product owner to create what Eric Evan called the ubiquitous language, a common dialect between the business and technology.

Make sure everyone is aware that a passing acceptance test suite means a green light from the business to release the software.

Practice 5 – be ready to roll back!

Be ready to roll back; sooner or later you will need to do it. Remember, You don’t need more QAs, you need a faster rollback. If anything goes wrong in production, the first thing you want to do is to play safe and come back to the last working version.

- Develop a rollback strategy and the process of what to do when the system is down

- Split non-backwards-compatible database changes into compatible ones

- Always use the same process of delivery for rollbacks and for standard releases.

- Don’t be afraid of bugs, the user won’t leave you if you react quickly!

- 🗨️ annot. - But they will you if you have consistent bugs in prod so TEST TEST TEST FAST FAST FAST OFTEN OFTEN OFTEN

Practice 6 – don’t underestimate the impact of people

You won’t automate the delivery if the IT Operations team won’t help you. After all, they have the knowledge about the current process. The same applies to QAs, business, and everyone involved.

Practice 7 – build in traceability!

- Log pipeline activities! In the case of failure, notify the team with an informative message.

- Implement proper logging and monitoring of the running system

- Integrate production monitoring into your development ecosystem.

Practice 8 – integrate often!

As someone said: Continuous is more often than you think. There is nothing more frustrating than resolving merge conflicts. Integrate the code into one codebase at least a few times a day. Forget about long-lasting feature branches and a huge number of local changes.

Practice 9 – build binaries only once!

Build binaries only once and run the same one on each of the environments. No matter if they are in a form of Docker images or JAR packages, building only once eliminates the risk of differences introduced by various environments.

Practice 10 – release often!

As the saying goes, If it hurts, do it more often. Releasing as a daily routine makes the process predictable and calm. Stay away from being trapped in the rare release habit.

Rephrase your definition of done to Done means released. Take ownership of the whole process!