Let’s Talk about Crowdstrike.

CrowdStrike is an EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) vendor. The purpose of this type of software is to monitor computers for malicious activity and respond to those threats. Since cybersecurity is constantly evolving, new risks appear all the time. To maintain security, EDR vendors push updates to keep their features and threat intelligence up to date.

CrowdStrike’s agent is what is known as a kernel module. The kernel itself is the core of the operating system, responsible for managing all aspects of the computer. Kernel modules are like add-ons to the OS that enable additional system functionality, but with this power comes risk. If something goes wrong with a kernel module, it’s treated as an operating system error. To avoid potential corruption, the system may crash as a safety measure.

This is what happened on July 19, 2024: CrowdStrike published an update that, when processed by their kernel module, caused an error triggering a blue screen of death on over 8 million Windows machines in less than an hour.

CrowdStrike responded to the incident by suggesting that such failures can happen to any company. While it’s true that “you can’t prove there isn’t a bug,” this situation is different. Founded in 2011, CrowdStrike was added to the S&P 500 in June 2024, earned over $500 million in 2023, and serves major global enterprises. Given its experience, it should understand the risks and maintain a mature software development process.

This incident wasn’t caused by a rare edge case, a unique data condition, or unforeseen product usage. It appears to be from a deprioritization of quality assurance, testing practices, and internal controls. The blue screen of death occurred on 100% of Windows machines, 100% of the time. This suggests that either no testing was performed on even a single Windows instance before the global rollout, or, worse, the testing results were ignored.

Unless very convincing evidence is provided, the global outage affecting airlines, grocery stores, banks, hospitals, and emergency services was likely due to the change not being tested before deployment to all clients.

This should go without saying, but testing on production-like or client-like systems is critical before releasing to production or client environments. While it’s impossible to account for every variation and variable, thoroughly testing your application changes is essential. For a client agent, at a bare minimum, you should validate every change against all the operating systems your software claims to support.

Unfortunately, some view quality assurance and testing as obstacles rather than safeguards or as a secondary priority. Hopefully, this event serves as a watershed moment, emphasizing that testing is an essential asset.

After testing, it’s time to deploy. Depending on the criticality of your software, it may be worth considering how you deploy in order to minimize the impact of any issues. There is a concept called canary deployment where you deploy a new change to a subset of clients and collect telemetry from new changes and watch for issues. Only after the canary group passes should you proceed with the release to all clients.

There is an extension to canary deployments called deployment rings. This concept builds on the idea of canary deployments by extending it beyond a single initial group. Various strategies can be employed within this framework, but the main idea is to segment updates into groups, such as Internal, Canary, General, Enterprise. You then progressively push the change to the next ring only after you are confident that the change is safe, limiting your blast radius if something goes wrong.

While these progressive deployments are useful in a Software as a Service (SaaS) environment, I believe it is critical to consider them when deploying to an external client environment. In most SaaS environments, the organization has direct access to their system, allowing them to debug, address, and resolve issues. In contrast, when deploying to a client environment, you are pushing changes to a system where you typically don’t have direct access to resolve issues that result from your software.

Let’s shift focus to the clients. Clients must also be prepared for disasters, even though CrowdStrike is clearly at fault in this situation. All companies—especially critical infrastructure—need to proactively consider risks and prepare for what might go wrong. It’s the old adage: “People don’t plan to fail; they fail to plan.”

I heard from an acquaintance whose employer was affected by the CrowdStrike incident. It turns out they decided to trigger their disaster recovery (DR) plan and switch from the primary to secondary environment. Quickly their secondary environment started to get the blue screen of death, since their it too had CrowedStrike installed and as the machines came online they too got the bad update. Despite the redundancy and having a DR plan, sharing a vendor between the primary and secondary was a single point failure.

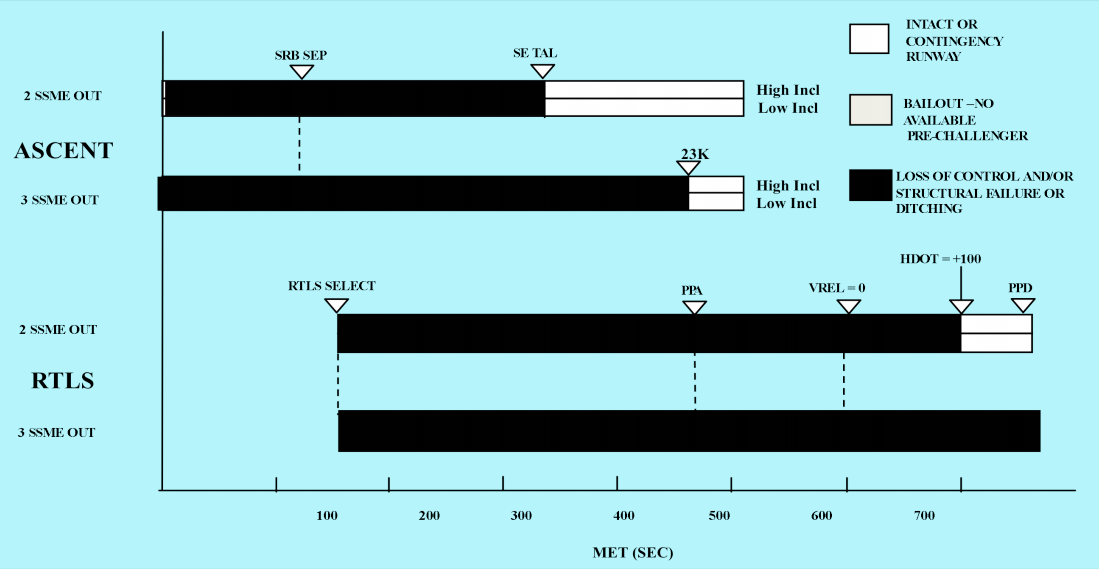

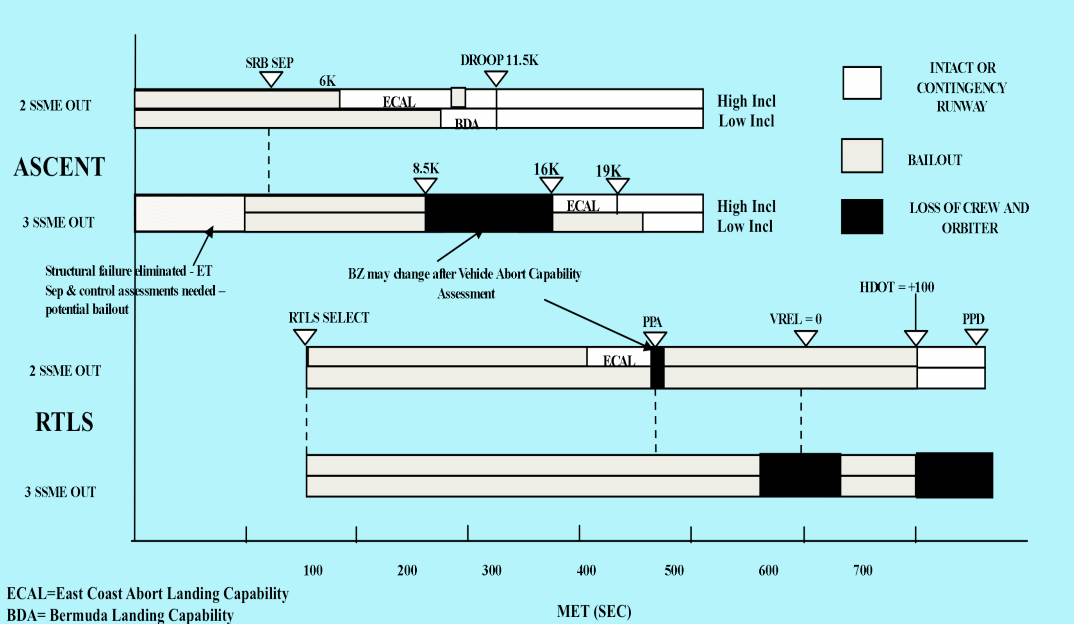

In rocketry there is a term called “black zones”, where if you have a failure, in a certain part, at a certain time it would result in the loss of the vehicle. Engineers and organizations need to understand their “black zones” and shared failure points and work toward reducing them. This can be accomplished with table top exercise and DR testing, where you map out your environment and understand each component, how it works, the criticality, and how you can handle its failure and if it affects other systems are your immediate or resolve the issue limiting your black zones.

NASA shuttle black zones: pre vs. post Challenger disastor.

One potential solution to my acquaintance’s issue is to keep a small subset of instances active in the secondary environment, rather than all machines spun down to save costs. If both environments fail, operators can investigate shared failure points and isolate the issue before bringing all resources in the secondary environment online.

In CrowdStrike’s case, had this setup been in place, the affected company might have realized that activating the DR plan would not resolve the outage. Instead, they could have identified the issue and blocked the faulty update from reaching their secondary environment through network rules.

All the takeaways we have discussed share a common theme: while they reduce risk, they also increase complexity, which, in turn, raises costs. Robust development processes and redundant systems are more expensive to operate, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Each product or service needs to strike a balance between its business model, criticality, and costs. This is the essence of engineering. As a quote I once heard on the Science Channel puts it: “Any engineer can build a strong bridge that’s easy. The hard part is building an economic bridge.”

The recent outage at CrowdStrike underscores the need for software vendors and service providers to grasp the extreme trust their clients place in them and the profound social responsibility they carry. Systems used by hospitals and emergency services, where access to accurate information can mean the difference between life and death, must be treated with the utmost seriousness. This responsibility must be internalized not just by CrowdStrike, but by all organizations managing critical infrastructure.x